|

Blue Pearl

|

Abalone Cultured Pearl |

INTRODUCTION

Attempts at culturing a blue pearl in the abalone have been in progress since Louis Boutan’s pioneering experiments in France during the early 20th century, and La Place Bostwick's unsubstantiated American experiments that he described in rather euphemistic terms in 1936. By the mid-50s, the Japanese researcher Dr Kan Uno had developed culture technology suitable for growing a half blue pearl in several species of abalone. A few years later, the Korean father and son team of Ki-Sun and Won-Ho Cho were culturing half pearls and keshi pearls in Korean species of abalone. Most recently, Canadian Professor Pete Fankboner has developed patented technology that is being used commercially to culture half-pearls in the Californian H. rufescens or red abalone. Quite independently, abalone pearls were cultivated experimentally in Tasmania, until this culture ceased due to financial difficulties. New Zealand is presently the home of at least two successful abalone pearl culture operations utilising the New Zealand paua, Haliotis iris (Martyn, 1784). These commercial operations are Empress Pearl Ltd and the Eyris Blue Pearl Company™. The story behind the creation of the Eyris cultured half-blue pearl, that is known commercially as the Eyris blue pearl, is as remarkable as each individual product. Roger Beattie, Managing Director of the Eyris Blue Pearl™ Company, has been diving since 1978 and during that time spent seventeen years as a commercial paua diver. He still holds the New Zealand record of 65 for the number of legal sized paua (over 125 mm) gathered in a single dive. Paua diving in New Zealand is restricted to free diving, with no underwater breathing apparatus allowed. Over the years Roger Beattie has played an integral role in the management of the New Zealand paua fishery. He was instrumental in getting a reseeding programme for wild stock paua up and running, and became interested in farming paua.

In 1989 he established the first ocean based abalone blue pearl culturing farm in the Whangamoe inlet on New Zealand’s Chatham Islands, some 800 km east of Christchurch. Until 1989 only natural abalone pearls were available for purchase, as earlier research to culture pearls in these molluscs had been abandoned because of the difficulties in both farming and nucleating abalone, a haemophilic univalve mollusc that has a large central muscular foot. Two years later, catastrophic death of stock, due to the combination of unusually heavy rainfall and protracted onshore winds prompted the need to search for a second location. In 1994, another farm was established in Akaroa Harbour on the Banks Peninsula. However, in 1996 an algal bloom wiped out 50 per cent of the paua on the farm. To reduce the element of risk to his stock Beattie decided to establish another pearl farm at Tory Channel in the Marlborough Sounds. Farming in three geographically isolated locations helps to minimise the risk of a disaster on any one farm.

ABOUT THE ABALONE

The abalone is a univalve mollusc that is a member of a primitive group of marine snails belonging to the class Gastropoda, sub-class Prosobranchia, order Archeagastropod, and family Haliotidae. It is one of the largest gastropods. There are over 130 species of abalone throughout the world all belonging to the genus Halitotis. Around the world, countries whose waters host various species of abalone refer to their indigenous species of Haliotis by local names such as abalone (Australia and the USA), aulone (Mexico), perlemoen (South Africa), and paua a name given to the New Zealand abalone by the Maori. In New Zealand the Maori gathered paua both for food and its shell that was highly prized both for decoration and jewellery. The New Zealand paua has the scientific name Haliotis iris, meaning rainbow coloured abalone. These molluscs are only found in the cool clear waters that surround the coastline of New Zealand. The paua is the species of abalone that displays the greatest range of colours, and the strongest iridescence from the nacre of any abalone.

Its anatomy

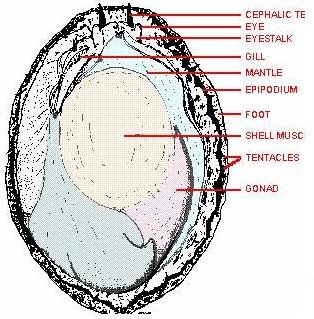

The internal organs of the abalone are held under and within its univalve shell. Figure 1 illustrates the major body parts of the abalone.

Fig. 1. Gross soft tissue anatomy of the abalone. After Cox (1962) |

Each abalone has a large muscular foot with a diameter similar to that of the shell itself. The muscle of the foot has two functions. First, it creates the strong suction that permits the abalone to attach firmly onto rocky surfaces. Second, an associated vertical muscle column firmly attached the body of the abalone to the undersurface of its shell. The epipodium, which has a sensory function, consists of small tentacles that extend from the foot and project beyond the edge of the shell in the living mollusc.

As the surface of this epipodium may be smooth or pebbly in appearance, and its edge may be either frilly or scalloped, it is the most reliable structure for discriminating species of abalone. The internal organs of the abalone are arranged around its foot and under its shell. This mollusc’s most conspicuous organ, its crescent-shape gonad, which is grey or green in females and cream in males, extends around the side opposite the respiratory apertures (pores) and to the rear of the abalone. The head of the abalone has a pair of eyes, a mouth and enlarged pair of tentacles. A long, file-like tongue (radula) in the mouth of the abalone is used to scrape agal matter of ~3x3 mm size from rocks for food. A feathery gill, located next to the mouth and under the shell’s respiratory pores, extract oxygen from seawater. This water is drawn in under the edge of the abalone’s shell, and then it flows over the gills and out though the pores. Waste and reproductive products (sperm or ova) are also carried outwards in this flow of water. The mantle, which surrounds the foot and body of the abalone and is closely adapted to the inside of the shell, is responsible for the secretion of the shell and its lining of iridescent nacre.

Since the abalone has no obvious brain structure, it is considered to be a primitive animal. However, it does have a heart on its left side and bluish coloured blood flows through the abalone’s arteries, sinuses and veins, assisted by the surrounding tissues and muscles.

Part 2 of Blue Pearl

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Learn more about ablaone pearls.