For decades, the Mississippi River town of Muscatine was the pearl-button capital of the world.

A man in the Muscatine shell-soaking room, about 1915. ALL PHOTOS COURTESY THE NATIONAL PEARL BUTTON MUSEUM

A Sift Through the Remnants of Iowa’s Forgotten Fashion Scene

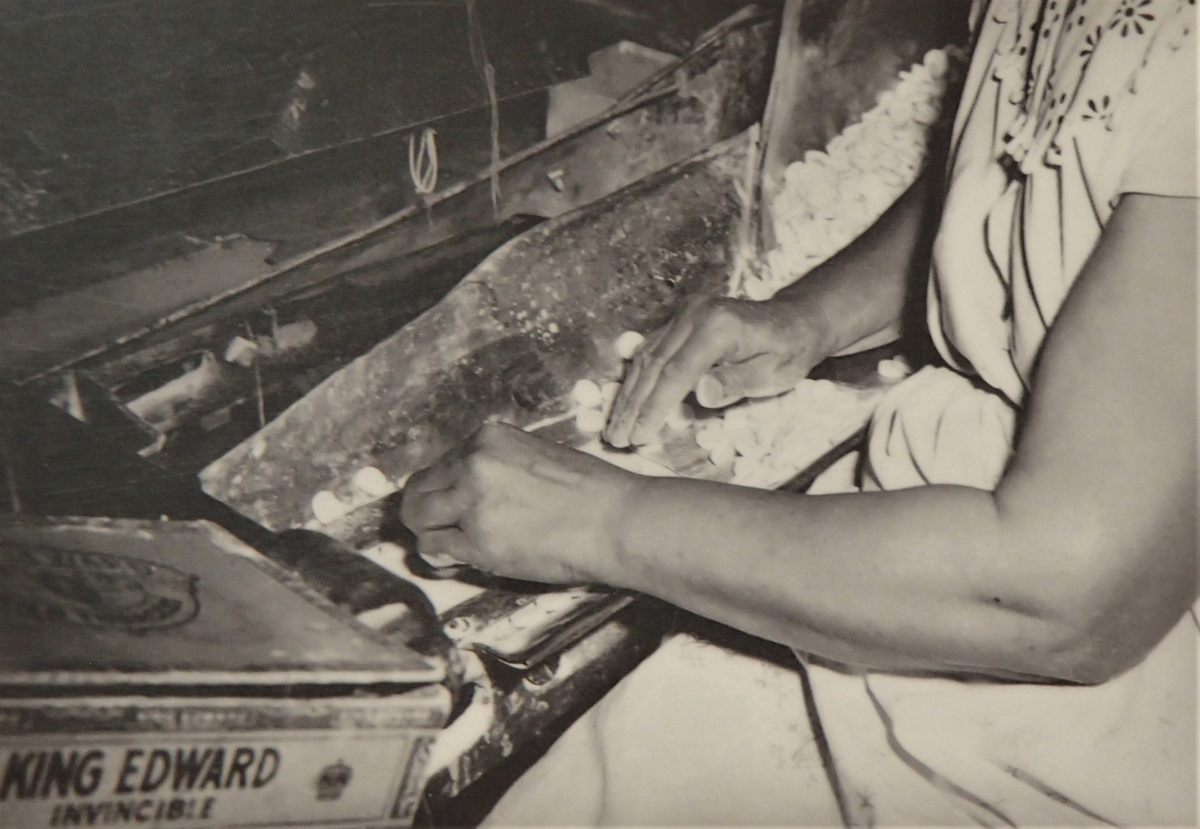

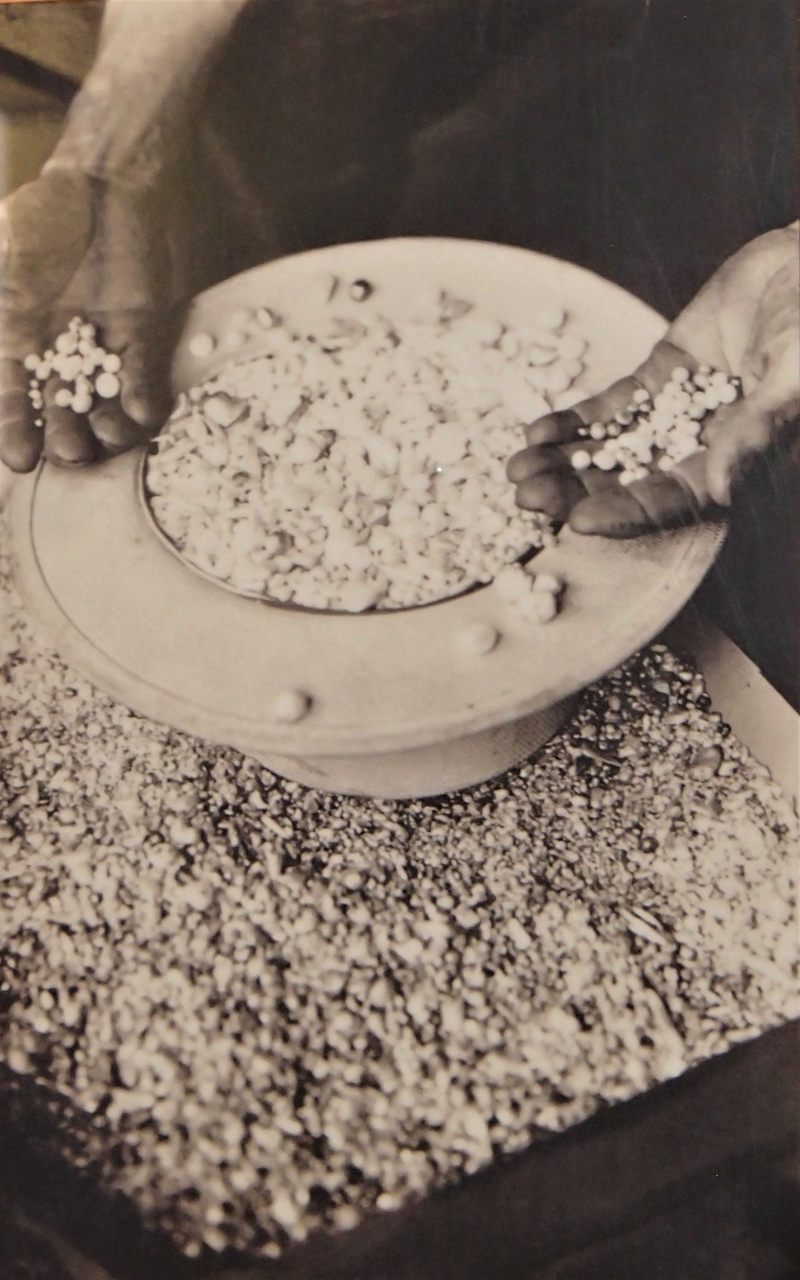

CLUSTERS OF CLAM SHELLS LIE on the banks of the Mississippi River in Muscatine, Iowa. Look closely and you’ll see each shell is dotted with perfectly neat holes. Many decades ago, these shells were plucked from the bottom of the river by the ton, soaked, steamed, and swept of their meat and pearls. Circular saws cut multiple discs out of each shell. These were called “blanks.” Each blank was sanded down into a perfect pearl button, ready to be sewn onto a dress, jacket, or glove.

Muscatine’s pearl button industry hit its peak between 1908 and the ’20s, when factories in the Iowa town produced 1.5 billion buttons, or one-third of the world’s pearl button supply. These buttons were worth $3.3 million, according to the 1910 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. But few of us who grew up along the Mississippi, who’ve held those milkweed-grey shells with holes in them, have actually held pearl buttons or heard a cohesive origin story about the industry. To get the definitive history I went to Terry Eagle, the former Director of The National Pearl Button Museum at The History and Industry Center, in Muscatine. “The story of the pearl button is a national growth story, a national treasure story, and an environmental lesson,” Eagle says. “And if you don’t believe me now, I’ll

As a kid, Eagle grew up hating the hole-filled shells leftover from the pearl button industry because they wouldn’t skip across the Mississippi. He used to work at the Muscatine Fire Department, where, at least three times a week, a parent would bring in their kid, who had their finger stuck in the holes of the blanks of the shells. “They were thought of as a navigational hazard, you couldn’t walk the Mississippi without cutting your feet,” Eagle says, “but Boepple saw the value in these seemingly worthless clams.”

That would be German button artisan John F. Boepple. In 1890, he came to the United States because a new German tariff on imported oceanic mother-of-pearl left him little room for profit. Pearl buttons were Boepple’s best sellers. He made buttons out of wood, bone, horn, and hoof, but they didn’t fly off the shelves like the pearl versions.

An acquaintance from the U.S. sent Boepple a mollusk from the Mississippi with “bark,” or an exterior that was milkweed grey. Inside the freshwater shell, Boepple found high quality freshwater mother-of-pearl, which resembled the high-quality oceanic pearl that Boepple used prior. Mollusk shells are coated with an opalescent substance called nacre. When an irritant like sand or rock gets inside the mollusk, the creature will coat the irritant with nacre and potentially produce a pearl.

Read more: Article source:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/pearl-buttons-muscatine-iowa

Join in and write your own page! It's easy to do. How? Simply click here to return to Mollusc News.